A cup of tea would restore my normality

A cup of tea would restore my normality

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,

Douglas Adams

Cecilia and Father Rodolfo walked back to his Trabant, and drove back in silence. When they returned, Ánibal was sitting in the taxi, parked in the alleyway beside the diocese office. When Cecilia and the priest got out of the car, Ánibal joined them as they walked into the office. He said, “are we all set to return to Havana?” Cecilia was too overcome to answer, so Father Rodolfo said, “There are some, uh, complications that require the señorita to speak with another priest regarding the information she seeks.” Ánibal looked down at his  Timex wristwatch, and shook his head. “This is no good: I must return to Havana tonight, or I will be in trouble with my jefe, my boss.” There were a moment or two of silence, and then Cecilia said, “Ánibal, I have kept you long enough. I will pay you the entire fare, and when my work here is done I will take the bus back.” Ánibal considered that for a moment, and then said “Yes, I guess that is what is best.” Cecilia reached for her wallet and drew out two, $50 bills. She handed them to the taxi driver, and said “Thank you and please thank Tia Consuela and Tio Fernando for their help and kindness.” Ánibal looked at the money as though it were manna from heaven. “I will do that, señorita Cecilia. And good luck with your search: I hope you find what you’re looking for.” I will bring your suitcase here before I go. With that, Ánibal went out the door, and Cecilia & Father Rodolfo looked at one another.

Timex wristwatch, and shook his head. “This is no good: I must return to Havana tonight, or I will be in trouble with my jefe, my boss.” There were a moment or two of silence, and then Cecilia said, “Ánibal, I have kept you long enough. I will pay you the entire fare, and when my work here is done I will take the bus back.” Ánibal considered that for a moment, and then said “Yes, I guess that is what is best.” Cecilia reached for her wallet and drew out two, $50 bills. She handed them to the taxi driver, and said “Thank you and please thank Tia Consuela and Tio Fernando for their help and kindness.” Ánibal looked at the money as though it were manna from heaven. “I will do that, señorita Cecilia. And good luck with your search: I hope you find what you’re looking for.” I will bring your suitcase here before I go. With that, Ánibal went out the door, and Cecilia & Father Rodolfo looked at one another.

Father Rodolfo picked up the telephone on the desk and dialed 326-4674. After a couple of rings, she heard a woman’s voice, asking “Si?” Father Rodolfo replied, “Padre Teodor, por favor. Esto es Padre Rodolfo.” “Uno momento,” replied the woman. Cecilia heard her put the phone down and walk away. A muffled conversation took place out of hearing of the telephone. There were more footsteps, and a man’s voice came on the line. “Padre Rodolfo, buenas noches!”. At the sound of ‘good evening’, Cecilia looked at her watch and saw that it was nearly 6 PM. The rest of the Spanish conversation between the two priests was too rapid for her to follow. After a couple of additional words, Father Rodolfo said, “Adios, Padre Teodor. Vaya con Dios.” He hung up the telephone and said “Father Teodor is expecting you. But he asks how long you intend to stay in Camaguey? Cecilia realized she had made no provision for a hotel in which to spend the evening. “I suppose at least until tomorrow. Could you assist me in finding a hotel?” Father Rodolfo replied, “Certainly. There is a place to stay a half block away from Father Teodor’s little house. I know the owner, and I will phone to make the arrangements. At this time of year, I’m sure she will have plenty of room.” “Thank you,” Cecilia replied. “Can you tell me how to get to Father Teodor’s house?” The priest replied, “I can do better than that – I will take you there in my little Trabant…shall we go?” As they walked out into the still-brilliant sunshine, Ánibal handed her the suitcase. Father Rodolfo took it and put it in the tiny trunk of the vehicle. Once again grinding the gears, they took off with a blast of  grey exhaust from the Trabant’s back end.

grey exhaust from the Trabant’s back end.

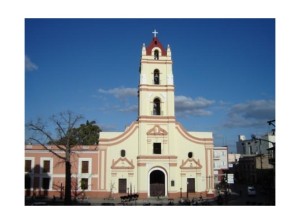

They drove to Bartólome Street, across from the  Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de La Merced. Bartólome was a quiet, tree-lined street with small homes and tiny shops. They passed a building on the left as the drove, and Father Rodolfo pointed it out. That will be where you will stay. It is really a bed and breakfast, but it is clean and the old woman that runs it will take good care of you.” As Father Rodolfo said this, Cecilia could have sworn there was a twinkle in his eye to accompany his little smile. Reflecting back on the notions she’d previously dismissed about priests and recent events, once again she felt a tinge of concern. But just then the Trabant stopped in front of a house, set back from the street with a small, wooden front porch. “Here we are, señorita,” said Father Rodolfo. As before, the priest opened her car door, then retrieved her suitcase from the boot of the vehicle. They walked together up to the front porch. An

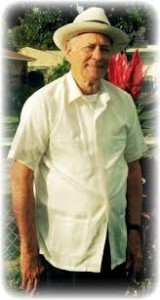

Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de La Merced. Bartólome was a quiet, tree-lined street with small homes and tiny shops. They passed a building on the left as the drove, and Father Rodolfo pointed it out. That will be where you will stay. It is really a bed and breakfast, but it is clean and the old woman that runs it will take good care of you.” As Father Rodolfo said this, Cecilia could have sworn there was a twinkle in his eye to accompany his little smile. Reflecting back on the notions she’d previously dismissed about priests and recent events, once again she felt a tinge of concern. But just then the Trabant stopped in front of a house, set back from the street with a small, wooden front porch. “Here we are, señorita,” said Father Rodolfo. As before, the priest opened her car door, then retrieved her suitcase from the boot of the vehicle. They walked together up to the front porch. An  elderly man dressed in a traditional guyabara shirt wearing a white fedora was standing just outside the door. The sight made Cecilia feel a wave of homesickness, as her grandfather always wore similar outfits. The man greeted Father Rodolfo warmly, then put out his hand to Cecilia. “I am Father Teodor, and you think you are señorita Vasquez?” Cecilia thought “what an odd thing for him to say, and then replied, “Yes, I believe I am and in fact I AM Cecilia Vasquez.” A second too late, she realized how rude that must have sounded to the elderly priest. But he took no notice, and after a second or two pause, he said, “So you are the granddaughter of the man who called himself Javier Vasquez? Well, well, frankly I am surprised he is still alive.” Cecilia experienced two feelings simultaneously: joy that this man seemed to know her grandfather, and a creeping sense of concern about the way he spoke of her Abuelo. “I don’t understand,” was all that Cecilia could say. “I’m sure you don’t, but it’s possible I can be of some assistance in clearing things up for you. Won’t you come into my humble abode?” With that, the two priests hugged one another warmly, and Father Rodolfo returned to his vehicle with a backward wave of his hand. Cecilia and Father Teodor entered the

elderly man dressed in a traditional guyabara shirt wearing a white fedora was standing just outside the door. The sight made Cecilia feel a wave of homesickness, as her grandfather always wore similar outfits. The man greeted Father Rodolfo warmly, then put out his hand to Cecilia. “I am Father Teodor, and you think you are señorita Vasquez?” Cecilia thought “what an odd thing for him to say, and then replied, “Yes, I believe I am and in fact I AM Cecilia Vasquez.” A second too late, she realized how rude that must have sounded to the elderly priest. But he took no notice, and after a second or two pause, he said, “So you are the granddaughter of the man who called himself Javier Vasquez? Well, well, frankly I am surprised he is still alive.” Cecilia experienced two feelings simultaneously: joy that this man seemed to know her grandfather, and a creeping sense of concern about the way he spoke of her Abuelo. “I don’t understand,” was all that Cecilia could say. “I’m sure you don’t, but it’s possible I can be of some assistance in clearing things up for you. Won’t you come into my humble abode?” With that, the two priests hugged one another warmly, and Father Rodolfo returned to his vehicle with a backward wave of his hand. Cecilia and Father Teodor entered the  house.

house.

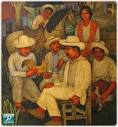

The small front porch gave no hint of the residence’s depth. Cecilia thought the house must have been built sometime in the 1930’s or early 40’s because of the architecture and layout, similar to the houses built in Miami in that era. It was filled with light, texture and color, both from native plants as well as the pictures that covered the walls. It was obvious Father Teodor, when he wasn’t attending to his priestly duties, was a collector of native art. Paintings, sculpture, antique furniture: it was all here and carefully arranged to be most pleasing to the eye. Cecilia said, “Father Teodor, your home is truly beautiful. “Gracias, senorita. I do enjoy all aspects of  Cuban vernacular art, and have roamed the countryside for years in search of it. Alas, it’s a dying industry, being replaced by trinkets, often that come from China or Vietnam and imported to sell to the tourists. It’s a pity the young people of today do not respect the ways of their elders.” Another wave of yearning broke over Cecilia, as listening to Father Teodor’s words reminded her so vividly of things her grandfather had spoken about when she was a young girl. The priest broke through her wistfulness, saying, “Please, come sit with me on the

Cuban vernacular art, and have roamed the countryside for years in search of it. Alas, it’s a dying industry, being replaced by trinkets, often that come from China or Vietnam and imported to sell to the tourists. It’s a pity the young people of today do not respect the ways of their elders.” Another wave of yearning broke over Cecilia, as listening to Father Teodor’s words reminded her so vividly of things her grandfather had spoken about when she was a young girl. The priest broke through her wistfulness, saying, “Please, come sit with me on the  back porch. There we can talk.”

back porch. There we can talk.”

Cecilia accompanied the priest to the back porch and they sat in adjoining wicker and native hardwood chairs. He began to speak, slowly and often searching for just the right phrases. “First, let me say that the story I will tell will most assuredly surprise you. You have family history of which you are likely totally unaware, as I’m quite sure your grandfather would never have spoken of it.” Since Cecilia had no idea what he was about to tell her, she could do nothing other than nod. Father Teodor went on. “Back in those days – in the 50’s under  Batista, young men in the village were divided into two groups: revolutionaries or informers. He stopped, and sighed. “People today don’t realize how good they have it here since the revolution. Life under Batista was always a guessing game of who will be picked up next for interrogation and possible imprisonment..or worse!” At this, he stopped speaking for several minutes. Cecilia looked over, concerned that something had afflicted him. But what she saw was a man who appeared to be wrestling with what to say, or possibly what to do. But then Father Teodor looked up, saying “Can I make you a nice cup of

Batista, young men in the village were divided into two groups: revolutionaries or informers. He stopped, and sighed. “People today don’t realize how good they have it here since the revolution. Life under Batista was always a guessing game of who will be picked up next for interrogation and possible imprisonment..or worse!” At this, he stopped speaking for several minutes. Cecilia looked over, concerned that something had afflicted him. But what she saw was a man who appeared to be wrestling with what to say, or possibly what to do. But then Father Teodor looked up, saying “Can I make you a nice cup of  tea, with good Cuban turbinado sugar, and lemons from my garden?” Cecilia said, “Oh, that would be wonderful. Yes, thank you.” The priest got up, and went back into the house, and around the corner into the kitchen. She could hear him opening cabinets, clinking cups on saucers, and running water from the faucet, apparently filling the teapot. Cecilia sat back in her chair, realizing how exhausted she was by everything she’d been through that day.

tea, with good Cuban turbinado sugar, and lemons from my garden?” Cecilia said, “Oh, that would be wonderful. Yes, thank you.” The priest got up, and went back into the house, and around the corner into the kitchen. She could hear him opening cabinets, clinking cups on saucers, and running water from the faucet, apparently filling the teapot. Cecilia sat back in her chair, realizing how exhausted she was by everything she’d been through that day.

The priest’s talk of revolutionaries stirred up emotions in Cecilia, of which she was unaware. She daydreamed about her Abuelo, dressed in the green fatigues of a  revolutionary, fighting for justice with Fidel and Che. She smiled at the thought, but her reverie was interrupted by the slamming of a door in the vicinity of the kitchen. Cecilia listened for a moment, and hearing nothing more, became concerned about Father Teodor. She got up from her chair, and walked into the house, quickly locating the kitchen. There she saw a tea tray laid out, with two cups, two tea bags, a small bowl of sugar and a carefully sliced lemon. The teakettle was whistling on the tiny gas stove. Not knowing what else to do, Cecilia removed the kettle, and poured the steaming water into her cup. After the tea steeped and she administered the lemon and sugar, Cecilia became aware that she was alone in the house. Apparently Father Teodor had stepped outside for some reason, possibly to fetch another lemon from the back yard? She took the filled cup, and returned to her chair to wait. She set the teacup on the small table between the two chairs to give it time to cool. While she waited, she again closed her eyes, but this time she fell into a half sleep. In this state, she had a different vision of events that may have taken place in the past. She saw her grandfather in the khaki uniform of a member of Batista’s army. He stood next to a line of soldiers with guns: a

revolutionary, fighting for justice with Fidel and Che. She smiled at the thought, but her reverie was interrupted by the slamming of a door in the vicinity of the kitchen. Cecilia listened for a moment, and hearing nothing more, became concerned about Father Teodor. She got up from her chair, and walked into the house, quickly locating the kitchen. There she saw a tea tray laid out, with two cups, two tea bags, a small bowl of sugar and a carefully sliced lemon. The teakettle was whistling on the tiny gas stove. Not knowing what else to do, Cecilia removed the kettle, and poured the steaming water into her cup. After the tea steeped and she administered the lemon and sugar, Cecilia became aware that she was alone in the house. Apparently Father Teodor had stepped outside for some reason, possibly to fetch another lemon from the back yard? She took the filled cup, and returned to her chair to wait. She set the teacup on the small table between the two chairs to give it time to cool. While she waited, she again closed her eyes, but this time she fell into a half sleep. In this state, she had a different vision of events that may have taken place in the past. She saw her grandfather in the khaki uniform of a member of Batista’s army. He stood next to a line of soldiers with guns: a  firing squad! Raising his arm holding a sword, her grandfather said “Listo! Apunta! Disparo!” The firing squad shot the green-clad revolutionaries lined up against the wall.

firing squad! Raising his arm holding a sword, her grandfather said “Listo! Apunta! Disparo!” The firing squad shot the green-clad revolutionaries lined up against the wall.

Cecilia jolted out of her nightmare, and shook her head. As she opened her eyes, she saw a woman standing before her, smiling benevolently. The woman appeared to be about her grandfather’s age, or maybe a bit younger. “Hello, uh hola..” Cecilia said with a slight smile. “Hola, replied the woman, her smile traveling to her eyes. Not knowing what else to say, and not sure if the woman spoke English, Cecilia said “Me llamo Cecilia.” The woman nodded, and replied “Me llamo Cecilia tambien. Yo soy tu abuela.” I am your  grandmother.

grandmother.